Introduction to Ecosystem Services Markets - Why Do Ecosystem Services Markets Exist? (Part 1 of 2)

The Soil and Water Outcomes Fund is one of several programs leveraging ecosystem services markets to pay farmers to implement conservation agriculture practices and to offer the resulting outcome credits (e.g., carbon sequestration and water quality improvement) to corporate and government entities to meet their supply chain or regional jurisdiction ecosystem targets.

This is part 1 of a two-part series to shed light on why ecosystem services markets exist, how they function, and how to engage in these markets. Part 1 focuses on introducing ecosystem services markets as a concept, explaining what they are, where they came from, and highlighting their key components. Part 2 will dive deeper into how regulatory and voluntary ecosystem markets operate to help identify opportunities to participate.

We have received a number of questions about ecosystem services and intend this series, and the related terminology glossary at the bottom of this article, to serve as a useful resource for agricultural operators and organizations.

The past few years have seen monumental shifts in commodity supply chains and the global economy. One of the more encouraging shifts has been the mainstreaming of ecosystem services markets related to carbon and water. These markets are quickly becoming recognized as ubiquitous and necessary tools in facilitating a transition to a cleaner and greener economy. Some recent bellwether moments are highlighted in Figure 1.

While the mainstreaming of ecosystem markets is a recent development, many have been around for years (such as the E.U. and California Emissions Trading Systems and the Chesapeake Bay water quality trading market). Others are relatively new to the scene, emerging in the 2020s (e.g., Soil and Water Outcomes Fund, Pachama, Regen Network, Ecosystem Services Market Consortium).

Given the amount of new information, historical context, and growing interest, it is important to understand and distinguish some of the important fundamental drivers underlying ecosystem services markets, including the answers to some critical questions such as: What are ecosystem services markets? Where did they come from? Who participates in them? What drives supply/demand? What does delivery mean in the context of an environmental asset? How does price discovery occur? What is the difference between a regulatory and voluntary market? And, how can they provide value to both end-users and producers of environmental assets?

Ecosystem Services Markets 101

The term ecosystem services was first introduced in the 1990s to define the benefits we derive from nature – including clean water, air, and biodiversity. These benefits are what economists like to call public goods, or goods that exist and are made available to all members of society.

Well-functioning and prosperous societies are often defined by a high degree of equitable and distributed access to public goods. However, there is a natural tendency to over-exploit our shared resources. Issues arise when access or distribution of public goods is constrained for the benefit of few to the detriment of many, such as negative impacts on the provisioning of food, increases in health hazards, and increased exposure to natural disasters.

Public goods have two defining characteristics:

they are non-excludable, i.e., you may be willing to pay to keep your water clean, but your neighbor will also benefit from the clean water without having to pay for it – also known as the Free Rider Problem.

they are indivisible, i.e., your neighbor’s overuse of water may benefit them, but limit everyone else’s supply – this is known as the Tragedy of the Commons.

To address these challenges, ecosystem services markets were designed to embed the negative impacts (called externalities) of individuals on natural resources into market-based systems which financially incentivize environmental stewardship, conservation, and rehabilitation of natural ecosystems.

Take, for example, the Acid Rain Program (ARP), a first-of-its-kind market-based program established in 1990 to address the acid rain plaguing North America in the 1970s and ’80s.

Established as part of the Clean Air Act Amendments (CAAA) proposed in 1989 by President George H.W. Bush and passed with bipartisan Congressional support in 1990, ARP was designed to curb three major threats to the nation’s environment and public health: acid rain, urban air pollution, and toxic air emissions. With EPA oversight, the ARP established a cap-and-trade system (see Appendix I: Definitions) which targeted the amounts of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides emitted into the atmosphere by coal-burning power plants in the U.S. – allowing them to buy and sell emission permits (called allowances) according to individual needs and costs.

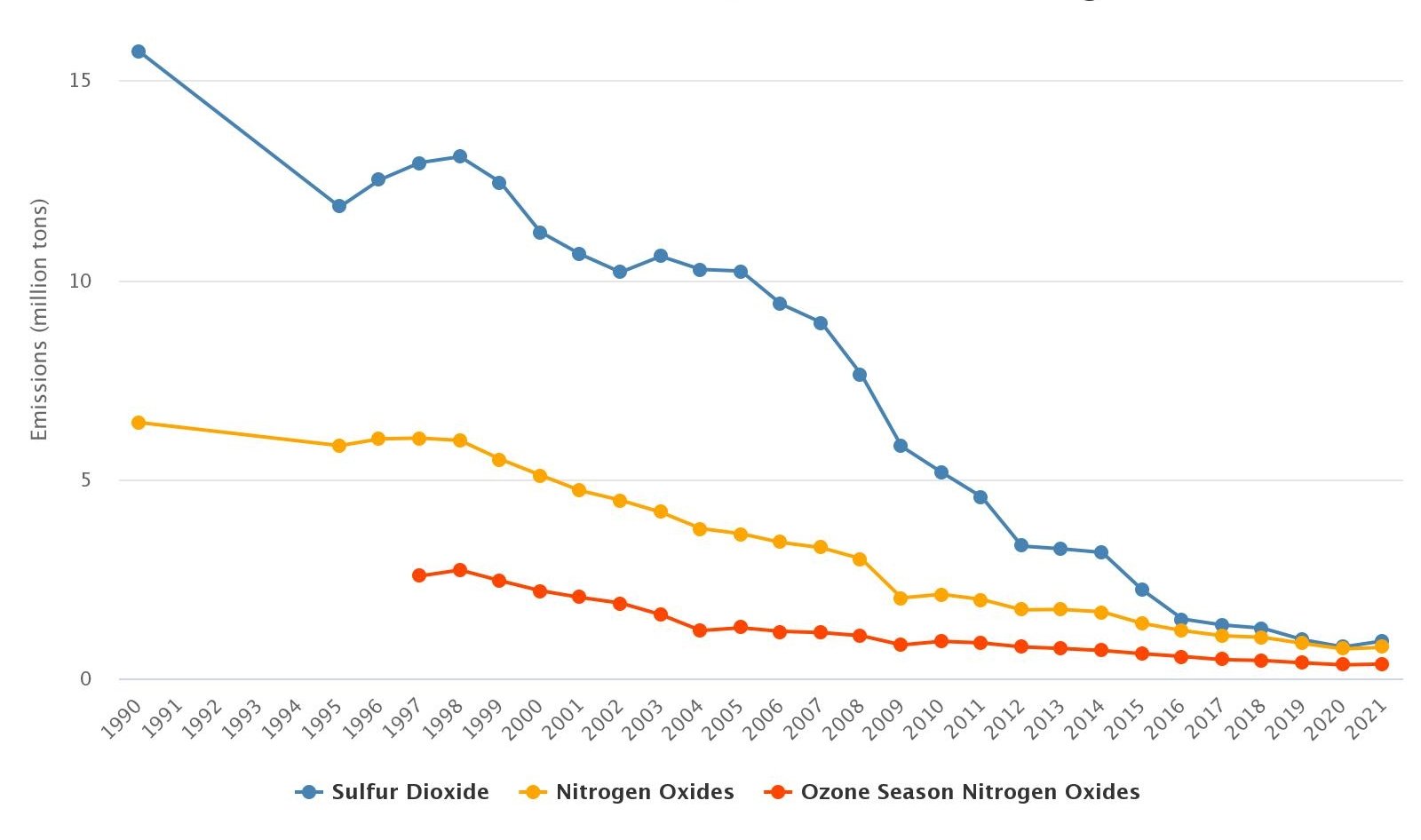

Figure 2: Emission Reductions under Clean Air Act

Source: EPA

In effect, this allowed the power plants to lower their emissions under the “cap” by trading (or buying allowances) from other plants that had excess allowances (having made reductions via direct investments in emissions reduction technology).

As Figure 2 illustrates, ARP has been resoundingly successful from both an environmental and economic point of view. According to the EPA, the estimated accumulated economic benefits from reductions in air pollution‐related premature death and illness, improved economic welfare of Americans, and better environmental conditions were almost $2 trillion by 2020. These benefits are more than 30 times greater than the estimated cost of compliance of $65 billion.

As demonstrated by the continued success of ARP, when ecosystem services markets are structured correctly, they have tremendous potential to deliver economic benefits, and incentivize and enable conservation, regeneration, and long-term environmental stewardship.

So, why did ARP work?

Critical Factors Necessary to Create Successful Ecosystem Services Markets

Successful ecosystem services markets, such as the Acid Rain Program, share some common design elements which influence and create the underlying market conditions required to align financial incentives with positive environmental outcomes. If any one of these design elements is not present, flawed, or not accurately accounted for, market failures (increased polluted air, water, and habitat) are likely to occur. These critical components include:

Non-localized environmental impacts – meaning pollution being addressed is a widespread issue, not just local. For example, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions for a power plant in California increase the GHG emissions across the globe. Polluted water discharged in public waterways impacts the water quality of everyone downstream.

Reliable and accurate data – data and the ability to accurately measure and monitor emissions or water pollution is paramount to effectively implementing a market-based system. Data should be verified by an independent third-party service to validate the integrity of the service and remove conflicts of interest. Without good data practices, there is no way to accurately determine supply/demand or enforce the rules of the market.

Target – a target can be in the form of a cap (i.e., the upper limit of emissions or load in the water context) allowed in a regulatory system, or a reduction goal (i.e., a voluntary pledge to reduce X amount of emissions or water use by a set date in a voluntary system). Targets are usually set by policy and regulation, less by economics, and they often become more ambitious over time. Ideally, a target is binding and carries severe enough penalties to incentivize compliance.

Scope of Coverage – to establish market liquidity it is important to have a sufficiently large market made up of numerous and diverse sets of entities with differing costs of compliance and reduction. This encourages investment in reduction strategies by some and trading to meet targets by others. A well-developed scope should include a standardized set of terms, definitions, operating rules, boundaries for activities, scientifically grounded methodologies, and units of measurement to ensure parties are managing to the same end-point of outcomes.

Cost containment – since the typical laws of supply and demand do not always underpin price, it is often a good idea for ecosystem services markets to have floor price and price volatility controls. These measures protect market participants and encourage investments in reductions strategies and projects that create a supply of credits for others in the system to buy/trade.

Enforcement – effective enforcement is one of the most critical aspects of a successful ecosystem services market. While this can be a daunting task, without it, the market often lacks incentives to operate efficiently and effectively. For this reason, most regulated (i.e., legally enforceable compliance) markets carry a premium price to their voluntary cousins.

Conclusion

Ecosystem services markets represent a relatively new and evolving market-based approach for aligning economic incentives to positive environmental outcomes. As the awareness of the impacts and risks associated with climate change grow, there is growing consensus these markets will play an ever increasingly important role in the transition towards a greener economy. For their role to be meaningful, their design and implementation structure must be well thought out to successfully deliver environmental and economic outcomes. Understanding the origins, intended purpose, and critical components of ecosystem services markets are vital for anyone considering participating in them.

Part 2 of this series will dive deeper into how regulatory and voluntary ecosystem services markets operate.

Appendix I: Glossary of Ecosystem Services Terminology

Allowances – an allowance is an interchangeable term used for a certificate or permit that represents the legal right to emit one unit of air (GHG) or water (nitrogen, phosphorus, etc.) pollutant. Such permits are used by companies or entities participating in mandatory regional, national, or international ecosystem services markets.

Cap-and-Trade – cap-and-trade is a common term for a government regulatory program designed to limit, or cap, the total level of emissions of certain pollutants, including GHG emissions and water nutrients. Any emissions produced beyond the cap result in a penalty (often financial). Organizations or projects in the scope of the system that produce beneficial ecosystem outcomes can generate credits that can be applied to reduce emissions against the cap. These organizations or projects producing credits also can trade (sell) the credits to other market participants who emitted over their cap and need to purchase credits to offset their emissions.

ESG – Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG), is a system for evaluating an entity or investment for its intangible assets such as its ability to create social benefits, help the environment, and promote diversity, equity, and inclusion (especially in the board room). Research consistently shows such intangible assets correlate with future enterprise value.

ESG Ratings – ESG ratings are designed to measure and quantify a company’s resilience and exposure to long-term, industry material environmental, social, and governance-related risks.

Ecosystem Service Markets – an ecosystem services market is an organizational structure for buying and selling units of environmental benefits and outcomes.

Externalities – externalities are a side effect or consequence of an individual or industry’s activity that affects other parties without being reflected in the cost of goods and services involved. For example, the cost of fossil fuels emissions on human health and the environment is not included in the price of gas at the pump.

Free Rider Problem – the free rider problem occurs when someone is allowed to consume more than their fair share or pay less than their fair share of costs, which in turn creates an inefficient distribution of goods and services.

Net Zero – a systems-based approach to the conservation of natural resources which encourages a sustainable balance between the impacts on the ecosystem and the public goods produced by it. In the context of carbon sequestration and emissions, net zero refers to a state in which the greenhouse gases going into the atmosphere are balanced by removal out of the atmosphere.

Public Goods – public goods are commodities or services provided without profit to all members of society by nature, governments, and organizations.

SBTi – the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) is a collaboration between several NGOs that works with organizations to define and promote best practices in emission reductions and net-zero targets in line with climate science.

Regulatory Markets – compliance markets use regulatory oversight and market-based mechanisms through the issuance of allowances (permits) and offsets to meet predetermined regulatory targets.

Tragedy of the Commons – the tragedy of the commons occurs when individuals pursue their own interests and neglect the well-being of society, usually by depleting a shared natural resource that then becomes unavailable for the whole.

Voluntary Markets – voluntary markets allow private investors, governments, NGOs, and corporations to voluntarily purchase ecosystem services credits to offset their unavoidable environmental impacts.